8 min. to read.

As we learn how to follow Jesus, we explore and experiment. Every spiritual journey is unique, because every one of our lives is unique. Yet, through this varied process we remain tethered to truth by the Bible.

The Bible can become a trusted and precious companion in our apprenticeship to Jesus. But simply having a Bible on the shelf won’t make a difference.

In the last post I suggested that you need to have a Good Bible. What is that? It’s a translation you will actually read.

That brings us, of course, to the question of translations. Which translation is the right one? Which translation is the most accurate? This is a long-standing and heated debate. Today, I’m going to tell you a bit about translations and versions.

If you have a lot of experience with the Bible, some of today’s material may be old news to you. Although, I’m often surprised when I come across life-long Christians who don’t know some of this. This post is long and a bit academic, but it definitely falls in the “Stuff You Should Know” category. It may even change how you think of the Bible!

The Bible is a collection of translated texts.

First, the Bible was not written in English. Unless you’re looking at ancient scraps of papyrus and scrolls, what you’re looking at is a translation. Every single Bible you can buy today is a translation.

Almost all of the New Testament was written in Koine Greek. This type of Greek is no longer spoken anywhere in the world—except in a handful of offices tucked away in the dusty back corners of seminaries. (Nope… it’s not even the same as modern Greek, spoken in Greece. It’s related, a bit like the relationship between the Anglo-saxon in the poem Beowolf and modern English.) A few small sections of the New Testament were written in Aramaic, a Semitic language related to Hebrew that is very likely the language Jesus and the disciples spoke every day. The Old Testament was written in ancient Hebrew.

Second, the Bible is not a single book. Many people just don’t know that the Bible is a compiled book. When you look at that leather-bound book on your shelf, what you’re seeing is not so much a book, but an entire library. It’s a collection of 66 books. Even several of those 66 books are actually collections of smaller groups of writings.

Third, every translation of the Bible is translated from a collection of texts. Because the books that make up the Bible were written in 3 different languages, by an unknown number of different authors, over a period of 1600 years, there is no single book in a library somewhere that contains all the original documents.

You can go into a Seminary bookstore (or Amazon) and buy bound copies of the Greek New Testament or the Hebrew Old Testament, but these are actually edited compilations. The best of the ancient manuscripts, scrolls, papyruses, and text fragments that exist have over many years been compiled together into these collections. These edited collections are what modern translators work from when they create a new translation or version[note There are several published versions of these collections that are widely in use today. The two most well known are the ISB text & the Nestle-Aland text. Almost every version you can buy is an English translation of one of these.].

So which version did God write?

Versions are completed translations of the Bible. When you hear someone refer to the New International Version, or the King James Version, that’s what you’re hearing about.

Each version was translated, either by an individual or most often, by a team of scholars. Each version used a certain collection of source documents, starting with one of the collections I mentioned above. Each finished version is published by a different organization. Each version was translated with a different translation perspective. All of these factors have some impact on the translation process, but what matters most to you is the translation perspective behind the version you’re reading. There are essentially three.

1. First, there’s what is thought of as a word-for-word translation.

This kind of translation is called “Formal Equivalence.” Here the translator is trying to match the best English word to the original word in Greek or Hebrew. One word for one word.

On the surface this sounds like the most accurate kind of translation. In some cases it is. But if you speak a foreign language you can immediately see the problem. Every language and culture have their unique phrases, idioms and grammatical structures that, if you translate them literally, make no sense.

For example, we have the phrase “kick the bucket” in English. A translator trying to convey this phrase in French would be completely wrong to use a literal word-for-word translation. The phrase doesn’t mean that someone literally knocked a bucket across the yard with their foot. It means that someone died. In order to translate accurately, you would have to leave behind word-for-word translation.

Translations done in this manner sound the most “Bible-y” and often read in a complicated and irregular flow. This is because they preserve the word-order of the original language, even when English uses different words order. For example, in Hebrew correct word order would be “arm of the Lord,” where in English it would be correct to say “The Lord’s arm.” So, word-for-word translations often require additional study and knowledge of the culture to get a clear sense of the verse’s meaning.

2. Second, there’s thought-for-thought translation.

This is called “Functional Equivalence.” Here the translator is trying to convey the idea behind the word or phrase in the most accurate way. This type of translation tries to strike the balance between conveying the exact original word, and the best phrase that will communicate the same idea in modern English.

For example, in English someone might say, “Michael shoots the ball.” Translating this into another language requires thinking through what to do with the word “shoot.” Are we shooting the ball with a gun? Shooting it out of a gun? Experienced English speakers know that’s not what we mean. We’re talking about throwing a ball, and not just that. We’re most likely talking about throwing a ball toward a basket in a game of basketball. A word-for-word translation would look for the word closest to shoot. A thought-for thought translation would try to convey the idea behind the phrase, focusing on throwing the ball toward the basket.

3. Third, there’s the “Dynamic Equivalence” form of translation, also called a paraphrase.

In this situation the translator is primarily concerned with the meaning. They start with the original text, but then instead of trying to translate word-for-word, they try to convey the original idea. They don’t try to preserve the original words or word-order, and focus instead on conveying the tone and sense of the text.

Dynamic Equivalent translations are often the easiest to read, but you just have to understand that they have a much higher level of interpretation baked in.

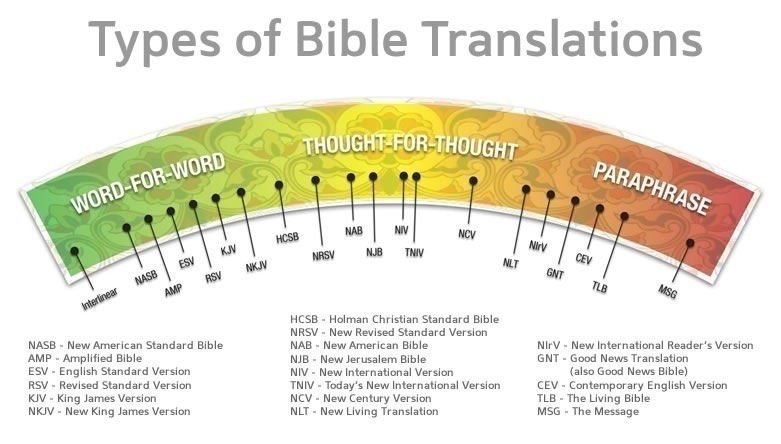

Here’s a quick reference showing 19 of the most common and popular translations and where they fall on this scale:

So, Which is the Best One?

The obvious question that comes up next is this: What kind of translation is the most accurate?

The answer? It depends.

- Word-for-Word translations are often most accurate to the original word choice, but can fail to convey the full idea of the text in the most accurate way. They also stumble when the meaning of specific words has dramatically shifted over time.

- Thought-for-thought translations are most accurate in many cases because they consider the cultural shift in words that has happened over time, but they can miss the nuance of specific words.

- Paraphrases can sometimes be the most helpful because they convey tone and emotive energy of the text, and can clarify context in ways that more literal translations can’t. But in helping provide easier comprehension, they can obscure some of the specific word choices in the original text.

So, with that completely unhelpful answer, which translation should you get for yourself? In the next post I’ll answer that question. I’ll also tell you why this whole issue doesn’t matter nearly as much as you might thing.

This post is in a 3-part series on the topic of Bible Translations.

Great post! I’ve done all my memorizing in KJV, but I use NASB a lot for study. I recently got a Key Word Study Bible which includes the Strongs numbers for the “important” words in the text and a complete Hebrew/Greek lexicon in the back! It is truly an old-school geek’s delight. I also like the infographic you included in the post.

It’s a joy to live in the internet age where all of these things are instantly accessible.

What do you think about the NET Bible? I appreciate the way it explains the translation decisions it makes by providing translation notes.

That really is the strength of it. I think in this internet-linked age all Bible translations ought to have an online version with links to editorial and translation notes. Heck — you could even like to original documents. That would really be great for personal study.

That would be incredibly helpful too. I’m sure someone is working on it at Logos or Accordance.

I would love it if one of the versions linked to the original documents and had digital images for you to look over. We’re not that far off from what you mentioned with what Dr. Wallace and others are doing at http://www.CSNTM.org.

Yea… That is good work there. I just think the internet provides a perfect medium for his. Imagine reading a passage in the NIV, say. You wonder about a certain word, so you click on it, and you get to see which textual variations stand behind that word, along with links to those actual source documents, as well as translation notes from the translators. Clicking deeper, you could see the etymology of the word, and its use in 1st century non-Biblical texts, for context. (Biblical dictionaries are terrible tools because they generally reinforce logical loops. The definition of this word is the definition of this word because that’s how we’ve always translated it… Most Biblical dictionaries give primacy to meanings that came to exist much later in the translation history of the word.) Something like this would really open up the text for people.

The only thing I don’t like about everything you wrote there is that I can see it in my head but can’t access it in real life. You sound like a visionary Marc. You should pitch the idea to the NetBible people and CSNTM. All the technology is already there but my guess is the primary inhibitor is funding.

I’d love it!

That was a very helpful post! thanks!

Glad to help! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Excellent job making the discussion of translations accessible. Blessings on your ministry.

Thanks, Alan! Glad it was helpful, and thanks for leaving a comment.

I really appreciate this article. I appreciated it when I first read it and I appreciate it even more as I look for my next Bible. Thanks for always being a great and trustworthy resource Marc.

Wow. Thanks for letting me know how helpful this was.